A Wolf in the Fir: Better than Two in the Brush

In 2002 I had the good fortune of being the Incident Commander on the Wolf Fire in Yosemite National Park. Started by lightning on July 11th, the Wolf Fire would end up as one of my seminal experiences in fire management. It was my first fire season of eight working on this amazing landscape, sculpted by both lightning and indigenous burning for thousands of years, before John Muir showed up. The fire started in a giant red fir upwind and downslope from the White Wolf developed area with a campground, rental tent cabins, and a small store. As was common practice in Yosemite at the time, rather than immediately suppressing the fire, it was evaluated for possible benefits to the surrounding forest ecosystem - a wildland fire use (WFU) incident. Despite the obvious concern about the developed area, fire monitors reported slow rates of spread with the occasional torching tree throwing spots downwind. This was typical fire behavior in the red fir ecosystem, particularly in this place of magnificent exposed fins and domes of granite. Fire effects monitors installed plots to measure fuel consumption and tree mortality, while firefighters prepared a plan with management action points (MAPs), including a structure protection plan for the developed area. The Wolf Fire would be free to roam.

2002 Wolf Fire Management Action Points

During the four months the Wolf FIre burned, the largest acreage growth in one day was approximately 100 acres. Its average daily growth over the four months was just over 16 acres per day. It was the largest fire use fire of the 2002 Yosemite fire season and burned until extinguished by rains on November 7th, with a final acreage of 1971 acres burned. Instead of becoming a negative recreational impact, the fire actually began to draw visitors to the White Wolf area, spurred on by a local newspaper’s reporting on the opportunity to see a fire up close. The most amazing thing about the Ranger-led fire walk was the realization by visitors that the fire was not a catastrophe, as most fires are portrayed in the media. Instead of fear, there came an understanding of the vital role fire plays in nature. There were no helicopters, no retardant drops, and no stern-faced, overly self-important officials extolling the virtues of mechanized fire suppression. Only the sun and bird songs accompanied wisps of smoke. Fire belonged here, and that was apparent to anyone who cared to investigate.

Fast forward to 2020, the Year of the Plague. COVID-19 was spreading in many communities, particularly among front-line workers, who could not shelter in place. Wildland firefighters were no different. Crew shortages were reported by Cal Fire in their inmate population, exposing yet another flaw with mass incarceration. Federal fire managers had been told by their superiors that this season “the predominant strategy” should be “rapid containment".” Which was interpreted by most as meaning there should be no “managed” fires - the sad current terminology for fires having resource benefit. As if other fires weren’t managed! The default response of suppression is, of course, heavily “managed.”

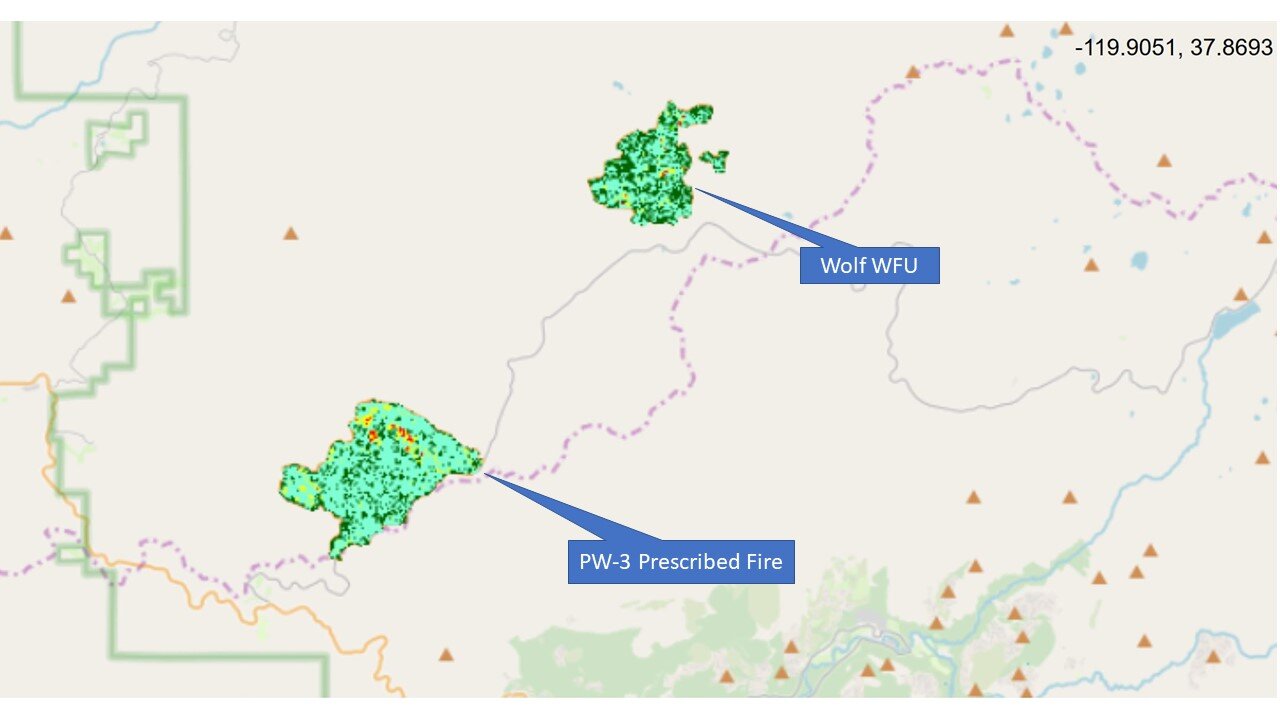

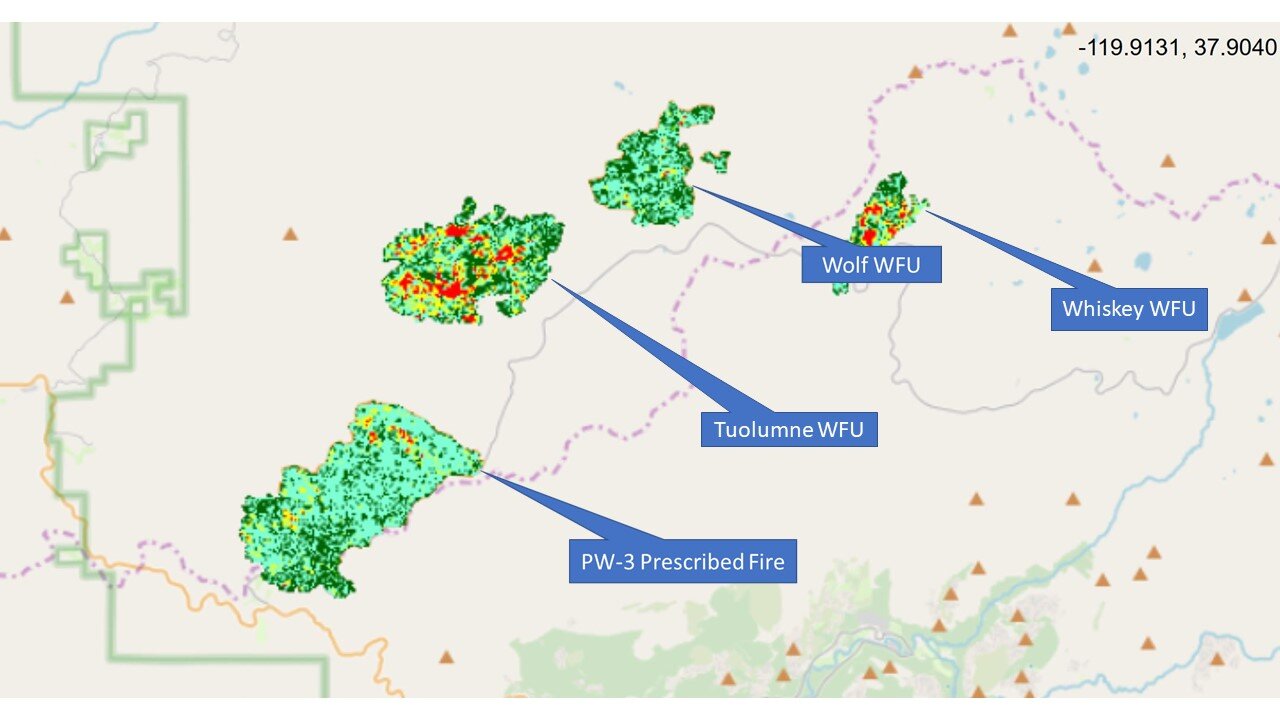

In spite of that, the well-experienced new Fire Management Officer at Yosemite, Dan Buckley, saw fit to not commit resources to a pair of lightning fires on either side of the Tioga Road leading up from Yosemite Valley to Tioga Pass. The Bluejay and the Wolf Fires. The Wolf fire lives again! Burning at over 8000’ and forced to wear the “confinement” suppression moniker for this year, this year’s fire was burning in the 2002 Wolf Fire footprint. Just past north of the infamous Spot 32 in the area shown below in the final 2002 Wolf perimeter map as “Spot 34.”

The story of Spot 32 is the infamous “catch and release” moment in 2002 when the Wolf Fire was threatening to encircle the developed area before Memorial Day. Park fire managers chose to extinguish that spot, waiting for White Wolf to close and clear out of visitors and staff. Then, after Labor Day, while engaged in a large landscape burn further down the Tioga Road near Crane Flat, managers relit Spot 32, freeing the Wolf Fire for a few more days before the rain.

I was returning to see the Wolf running free again, building on the past success, and I would revisit and pay homage to Spot 32. Now is a great time to see Yosemite. Due to the COVID virus numbers are greatly reduced for day visits, but one can still get a wilderness permit and go touch a forest fire. I came through the south park entrance and showed my permit. Soon I was walking into White Wolf from the Tioga Road. The entire area was closed. The White Wolf Lodge was gettng a new paint job, and it seemed the deserted campground was letting out a sigh of relief with no impact for the season. I could hear a ghostly babel of children screaming, car doors slamming, dozens of crackling fires, and general murmur that arises from a busy campground. The firefighters in 2002 camped here among the park visitors. Not this year. As I left the road for Harden Lake, suddenly I was there - Spot 32. I picked my way though the dead and down, moving crosscountry and off-trail, hoping to avoid any stray firefighters. There were a couple, not digging line, but simply monitoring the situation and acting as trail guards. I looked at my feet and suddenly there was a bedrock mortar, used by people in the past for grinding of grain, acorns or other food products. I felt a presence, a coming home, as something was lifting my head upward a couple of steps forward, and there was the smoke!

I lingered for over an hour, wandering around the edge of the fire, being mindful of falling snags. The “ka-thoomp” of falling snags reminded me of how that sound made all the White Wolf visitors nervous, especially at night in your cozy tent. There was an air of wildness that was like the scent of ozone, after a lightning strike. And I was back. I dodged the afternoon reconnaissance flight of the park helicopter visiting from Crane Flat helibase, furtively ducking under cover. I never saw the monitors and returned to my car, feeling exhilarated. The fire was cleaning up the surface fuels, leaving the large diameter red fir to continue their best mission of sequestering carbon. I felt sorry for those who could only view the forest through the extractive lens. As mass chaos was just beginning as all the fires in the foothills around the Bay Area and elsewhere in California took off, a fire was quietly benefiting the land. It was building resilience among old mature trees to future climate-driven fires, and creating a fuel break for subsequent fires, all with only the minor exposure of a handful of firefighters. Instead of deferring risk to future generations, as has been our habit, a small risk is taken even in the midst of our generation’s greatest pandemic. This fire also exemplifies this year’s USFS direction to “Commit resources only when there is a reasonable expectation of success in protecting life and critical property and infrastructure.”

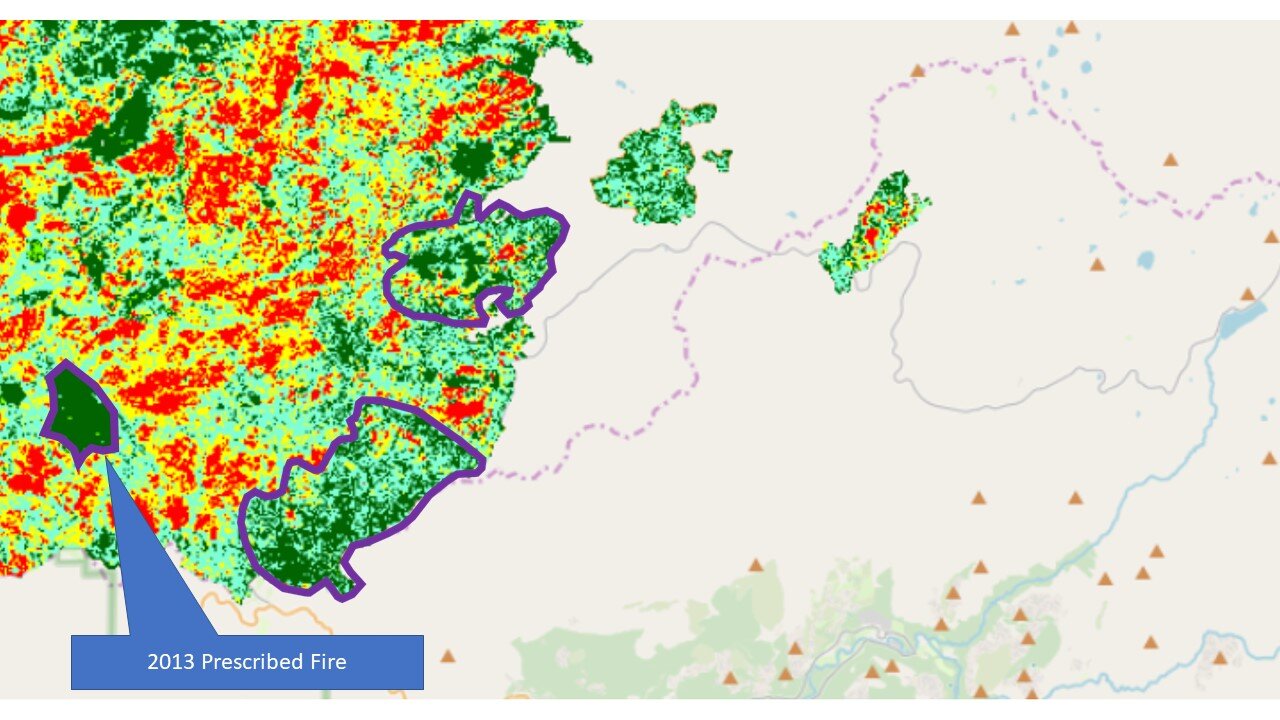

The Wolf Fire burned with largely low to moderate severity (green colors) in 2002 as shown in the slideshow below. The large prescribed fire by Gin Flat is also shown from that year, then the completion of that project in 2005, as well as a pair of WFUs from 2003 with a bit more high severity (yellow to orange). It’s clear in the devastating 2013 Rim Fire, even from this raw severity data, those earlier fires moderated fire behavior in the Rim Fire. Another prescribed fire, conducted in early 2013 near Hodgdon Meadow, before the Rim Fire, also show as a large area of low severity (dark green) after the Rim Fire. Getting fire on these dry pine landscapes and keeping it there as a routine matter holds the key to reducing emissions, building resiliency, sequestering carbon, and returning fire to wild landscapes. There are many who believe that fire is a natural component of wilderness and that fire (and smoke) should not be excluded from the wilderness experience. Yosemite National Park hopes to preserve that type of experience not only for visitors, but more importantly, for the health of the forest, itself. Logging will never replace fire as a disturbance in wilderness and roadless areas. A majority of fires in California this year are in grass and brush, anyway, so no amount of “active forest management” would make a difference.

Using fire through both prescribed burning and allowing some lightning fires to spread can be done with less exposure to firefighters and flight crews, and it can be done at less cost. Blanket bans on prescribed burning and “managed” wildland fires are a wrong-headed nod to those that would drag us back to the failed “10:00 am Policy.” It’s the kind of thinking that is OK with over a thousand firefighters and bulldozers in the Trinity Alps Wilderness earlier this year on the Red Salmon Complex. Now, with the siege of fires occurring around the Bay Area, we are bombarded with militaristic lingo like “battle rhythm” and “war zone.”

Focus the suppression resources around the high values at risk and be prepared in the wildlands to work with fewer resources and more sophisticated risk management, as is now the reality on California fires in the Golden Trout and Yolly Bolly Wilderness areas. It’s best for the land and it’s best for the firefighters.